Woodcutters of the Deep South - Michael Rogosin interviewed by Tanya Goldman

Thank you Tanya Goldman for the fascinating interview with Lionel Rogosin's son Michael regarding his work on restoring his father's amazing legacy and creating one of his own with amazing documentaries about each of Lionel's films. Lionel and Michael Rogosin's films are distributed by Milestone.

An Interview with Michael Rogosin by Tanya Goldman.

Michael Rogosin and his son Elliott with Martin Scorsese.

Michael Rogosin has been working tirelessly to support the legacy of his father, groundbreaking filmmaker Lionel Rogosin, best known for his landmark nonfiction films On The Bowery (1956) and Come Back Africa (1959), both available from Milestone Films. Since 2004, Michael has painstakingly researched the production of each of his father’s films, producing an accompanying documentary for each in the process.

Michael’s newest film—currently in its final stages—is a film that explores the rarely seen Woodcutters of the Deep South (1973). Below Michael speaks with Tanya Goldman about his father’s career and the context of this important film production.

To fund his project, Michael has turned to Kickstarter. Please visit this link for more information:

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1268129732/working-together

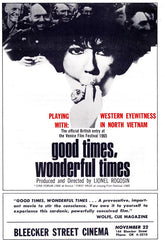

Tanya Goldman (TG): Can you describe the state of your father's career after the release and his adhoc distribution of antinuclear armament film Good Times Wonderful Times (1964)? I believe he toured the United States with the film and screened the film on numerous college campuses. As I understand, his difficulties distributing Good Times were one of the main reasons that led to his decision to found [independent distribution company] Impact Films.

Michael Rogosin (MR): Good Times was completed in 1964; shot and edited in London. When my father returned to the U.S. from his travels in making the film, he realized he was in trouble because it was a very expensive film to make, and there was literally no possibility for major distribution. At the time, no one in the U.S. would show an anti-war, anti-nuclear film. He was finally invited to the Venice Film Festival in 1965 and then got a slot at the Carnegie Hall Cinema in New York City in 1966. Then that was it. My father was under great financial pressure and, with the brewing war in Vietnam and my father’s concern about the possibility of an atomic war, he was desperate to get Good Times shown. The Bleecker Street Cinema [which he owned at the time] didn’t provide any consistent and regular income. There was also an attempt, with Jonas Mekas and Shirley Clarke, to start a chain of Bleecker Street-type cinemas but that never took off.

I don’t know the exact way that Impact Films started but it was certainly, at the beginning, a way to get Good Times shown. Since conventional theatrical screenings were impossible for this type of film, he assembled a small team of people and they pursued alternative possibilities—which, at the time, were largely college campuses. On campuses, the screenings were quite a success; one can say part of the growing anti-war movement, considering that a great number of students saw and were affected by the film. My father had described this period of his life as being extremely difficult but, also, exhilarating. I would add that there were also political activities and films being shown at Bleecker Street. But Good Times and Bleecker Street truly took over his creative life at this time, so that he was unable to make any other films for quite some time.

TG: What brought your father to his next string of projects—what we might deem his “American race trilogy”— Black Roots, Black Fantasy, and Woodcutters of the Deep South?

MR: My father had always been concerned or, should I say, obsessed, by racism and anti-Semitism in America. He made Come Back Africa because coming out of WWII, the apartheid legislation in South Africa was intolerable to him. Nonetheless, he was also very preoccupied with the fate of the black population in America.

The only support he could find to make these types of films was, ironically, from Swedish television and he was able to assemble a small budget for Black Roots [the first film in the trilogy] with support from Sweden and a little more from British Television (Channel 4). They were also funded by any small donations my father could get.

So, with that, he was able to make what he considered the first installment of his trilogy, though these works were never presented as one until now. In presenting these films together—with the addition of my films—we are trying to fill in and connect the points that these three films provoke.

TG: Yes, these films seem to have taken on a renewed relevance here in the United States given recent events. Now, can you tell me a bit about more about the backstory of Woodcutters.

MR: Working Together [Michael’s documentary on the film] will explain how my father got involved with the woodcutters organizing efforts and its connections to Come Back Africa. He learned of the woodworkers from Rev. Francis Walters. Francis had been the assistant to anti-apartheid minister Michael Scott, who had helped my father (along with Father Huddleston) film in the church quarters in Sophiatown, South Africa, in 1957-58. Francis Walters was invited to the first screening of Come Back Africa at the United Nations in New York City in 1960. Walters later remembered the film and called my father in 1972. My father immediately jumped at the opportunity to get involved.

TG: With [his more well-known works] On The Bowery and Come Back Africa, your father strove to immerse himself in his surroundings and closely collaborate with the films' participants. Was this the case with Woodcutters too?

MR: The methods in the new films were different from On The Bowery and Come Back Africa as my father had very small budgets—even in comparison to these earlier works. They were also very different from Good Times [an archival compilation film]. The three films of the trilogy all have slightly different backgrounds…

For Black Roots, you can say that my father’s method of knowing the people in his films intimately was largely the way he worked. From his efforts in the civil rights movement, he already was very close to several of the people in the film, particularly to Flo Kennedy, who was one of the most important black civil rights and feminist lawyers of the time. We explore who these people were in my documentary and their connection to my father. The other people in the film were people in the same movement, and they all considered my father as part of their group. So, yes, I would say that he did use his method of extreme empathy for the people in the film and collaboration, but in a different way from his earlier works. He was also spending a lot of time with the participants outside of shooting.

Black Fantasy, a sequel of sorts to Black Roots, deals with the psychological effects of racism on sexuality. Jim Collier is featured in Black Roots and became the main character in Black Fantasy. Jim had an intimate relationship with my father. There are some extraordinary authentic moments in this film, which were totally taboo at that time but, because of my father’s friendship with the participants, were totally natural.

TG: As is the case with many of your father's films—and many progressive nonfiction works of this era—these films found greater acceptance abroad, correct?

MR: Besides being shown on European television, and in several rare occasions as part of retrospectives and festivals, these films have hardly been shown anywhere!

TG: What are you envisioning the final shape of your accompanying documentary, Working Together, to take? Will this be different from your earlier films?

MR: Working Together will complete what I call my “Lionel Rogosin Film Cycle,” which is a film about each of my father`s films. The first three documentaries I completed on my father’s films [those for On The Bowery; Come Back, Africa; and Good Times] had a certain unity of style, where my father tells a good part of the stories and methods first hand through interviews. However, in these new films, we don’t have this material [Lionel Rogosin passed away in 2000] so I use other methods. Plus, my way of making films has changed over time and is, of course, responsive to the materials we can gather.

Bitter Sweet Stories, my documentary on Black Roots [included with the Milestone edition of Come Back, Africa], was—besides recounting my father’s work and filmmaking process—a series of portraits about the people in the film. In all my films, I situate where my father was in his creative process and the social and political aspects of the films as well.

Toeing the Line, my documentary about Black Fantasy, is complete and waiting for its final release, when all the restorations of my father’s films are completed. It is different in style from the other documentaries I’ve worked on. Collier, who was the main character in the original film, is the main character in my documentary many years later.

In Working Together— based on a rough test edit review of the materials I have now—we will go very far into subjects that are only implied in the original film. These have also become clearer as I researched my father’s notes and diaries about what happened to the Civil Rights Movement. So it will be a complex film that will cover a lot of ground. Our goal is quite ambitious because the idea that the oppressed can provoke change by working together across all kinds of barriers remains explosive even today—especially considering what is going on in America now. As such, I feel my father’s films remain extremely vibrant and necessary today. I’m guessing this project will be a 60-90 minute film, done on a very tiny budget!

TG: Do you have plans in place yet to screen Woodcutters?

MR: Yes; all my father’s films with my documentaries will be released on Milestone Films. I would also say that the goal is to do a major worldwide retrospective of all the films and my docs and the photography collection at major venues such as the Pompidou Museum (Beaubourg ), MOMA, and these types of museums/institutions.

TG: After the completion of Woodcutters, your father shot Arab-Israeli Dialogue (1974) and two other shorts [Oysters Are In Season and How Do You Like Them Bananas?], which are outliers among his oeuvre given their comedic tone. What has it been like researching these films?

MR: Working Together is the final documentary in the cycle. I have completed works on both Arab-Israeli Dialogue and the two shorts. Both of these films are also finished, but unreleased, as I plan to have them accompany the original films on a DVD/BluRay release. They are also both very different from the other documentaries as they are more personal. I actually appear in these films and take the viewer through these stories.

Because I completed these projects first, there is the influence of these more personal films in the footage shot for Working Together. I am in this documentary too, but not as the person who takes viewers through the film; I am a secondary character. Bob Zellner—the legendary Civil Rights activist who appeared in the original film—is the person that leads us through Working Together.

TG: I've often puzzled over the decision behind your father's two comedic shorts, they are just so different from his earlier works. Do you think this was at all motivated by his frustrations in distributing his activist works?

MR: Yes, you could say that, but he also had other creative aspects that he never explored. He had quite a good sense of humor! However, it is clear to me that he was totally driven by the questions of humanity and a concern for the oppressed.

TG: Thank you for your time. Is there anything else you'd like to add?

I would add that, after finishing the project, the goal is to have all the films restored and released on DVD/BluRay. I also hope to incite institutions and collaborate to hold larger retrospectives of my father’s work.

After Working Together is finished, I plan to finish a very personal project, a film that covers my father’s life and work but also explores our extraordinary family and my relationship with my father. It covers a lot. It is already three hours long…and I expect it to be around 6-7 hours when finished! Since it will be so long, it may be broken up into some sort of series. I’m tentatively calling it You Never Know.

Lastly, I find that people want to put a label on the documentaries on films that I am making and label them as “making of featurettes.” To me, any subject working with the tools of cinema can make cinema; these tools can be used in any way to make an effective film. So that is why I prefer to call my films “films on films.” They certainly cover the production history of each project but I also try to transcend that by producing works that add to the original works and say something of their own.